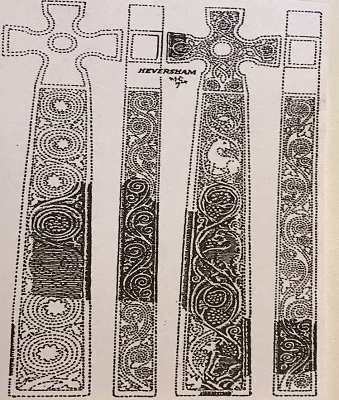

In the 1920’s, W B Collingwood completed a major study of ‘Northumbrian Crosses of the Pre-Norman Age’, and this included his detailed analysis of the cross shaft at Heversham. He made a drawing reconstructing the cross with the remnant included.

He acknowledged it to be a high-status Northumbrian grave marker and later stated that ‘the little foxes that spoil the vines, with bushy tails and pricked ears, are work of that first great English School of art taught by Italian masters in the 8th and 9th centuries. We shall travel far before we see the likes again.’

When ‘planted’ in the churchyard, it would have been approximately three metres in height and carved on all four sides, placed in a prominent position so that it could be seen from a considerable distance.

The Reverend Calverley was effusive in its praise: ‘It is particularly interesting to find the remains of a very beautiful piece of sculpture of pre-Norman date upon the very site on which it was first set up, amidst so many evidences of the state of the country about the time of its erection, and in the neighbourhood of dedications to St. Oswald and St. Wilfred’.

Calverley supposed it to be a ‘preaching cross’. He suggested that the carvings were similar to those found at Ruthwell and at Bewcastle, closely associated with the ‘Hexham School’ but not necessarily produced there.

Part of the ‘preaching cross’ at Halton in the Lune Valley

Collingwood argued that, by its basic design, it was shown to be a ‘grave marker, late Anglian, but not later than the Norse arrival’.

The first intention of a grave monument was symbolic and not just for decoration. Collingwood stated that, by the 8th century, ‘already the Vine had become the Tree of Life and a purely Christian emblem’ and that, ‘in the whole of Christendom the populated Tree of Life was familiar – no more is needed to suggest the bird and beast scrolls’.

Its design was thought to parallel other Anglian sculptures at Lancaster, Heysham, Lowther and Hoddon, possibly produced by a school of sculptors at Lancaster or Heysham ‘where there was a Celtic church and also suitable stone.’

He also suggested possible links to Halton, Kendal and Urswick, and even as far as Waberthwaite on the west coast of Cumbria.

The characteristic feature of an Anglian cross is that the cross head is always free-armed and takes the form of Saint Cuthbert’s Pectoral Cross.

Preaching Cross at Halton showing the ‘typical’ Anglian Cross Head

We do not know why, or when, the cross was broken up – we can but speculate.

It is possible that, since the Normans disapproved of many Anglian practices, considering them pagan, they could have demolished it.

However, a small fragment of the cross head is built into the outside wall of the late 14th century south aisle extension; this could of course be a much later ‘repair’.

A further possibility is that it was taken down during the incumbency of Edwin Sandys, Vicar of Heversham in 1542, born into a local family at Graythwaite, later to become Bishop of Worcester, Bishop of London in 1570 and Archbishop of York in 1576. He was ‘an early confessor of the protestant faith’ and it is known that he ordered the destruction of the standing stone cross at Kirkby Ireleth across in Low Furness, and possibly the Tunwinni Cross and the Norse Cross at Great Urswick.

What is clear is that, when Samuel Cole was made Vicar at Heversham during the ‘Commonwealth’, had the cross still been standing, it would almost certainly have been taken down then. Cole had fought on the Parliamentarian side and ‘could be depended upon to support Presbyterianism’. It was during this period also that the Standing Cross at Beetham was broken up.

Although during the ‘Commonwealth’ the Puritans would have regarded it as being idolatry there is no firm evidence that they took it down, although this is the most likely explanation.

At some stage, the surviving fragment had been cut and re-used for some other purpose, probably inside the church, and prior to its recent relocation had rested for at least 150 years in the church porch.