Humphrey Head Point looking into Morecambe Bay

There is a likely Celtic settlement here, adjacent to a Holy Well. It marks the ‘gateway’ into the Kent Estuary; Heversham can be seen from here looking up the Estuary.

It is believed, and supported by Lidar technology, that the first simple Celtic monastery at Heversham was on the site of what is now Heversham Hall, which was almost ‘islanded’ by the undrained marshes. The monks would have engaged with the sparse population and small settlement working the land, offering pastoral care, and preaching around a simple wooden cross on our present church site. The site would have been ‘consecrated’ by the burial of the dead.

Lidar image of Heversham Hall

After the Synod of Whitby in 664AD, at which the ‘Roman Church’ was given precedence over the ‘Celtic Church’, many Celtic monks and important Anglian sympathisers withdrew from the North back to Ireland. This led to significant changes at the monastery which, over time, was required to adopt the Benedictine Rule and its resident monks to withdraw from the world.

As an incentive to accept the bishopric of Hexham in 685AD (which he swapped for Lindisfarne), Saint Cuthbert was offered large estates in and around Carlisle and Cartmel, including all the Britons in them! It is most likely that our area was included in this ‘gift’ and the association with Lindisfarne continued thereafter.

By the first decade of the 8th century, Heversham had become the only Anglian minster ‘at the bottom of Westmorland’ and was linked to the Bishops of Lindisfarne. A small ‘village’ grew up around the minster to ‘service’ the monastery.

Whilst required to turn their backs on the outside world, the monks were expected to lead worship in the surrounding area, initially around carved wooden crosses, and later in small chapels. They also continued to bury the dead.

As time went on, the minster attracted important sponsors and major landowners and had strong links with the ‘key’ monastic ‘hub’ at Lancaster, and the Abbot at Heversham probably had oversight of the Cartmel community.

At some stage in its development, it probably erected a small stone building on the present church site for local worship, instead of continuing to gather around a wooden cross.

Life would have changed very little over many years for the local population, who had a subsistence- level existence on the land and the estuary, and whose lives were dependent on the ‘good offices’ of the minster. The changes and chances of the wider Northumbrian kingdom would have minimal impact locally, except for perhaps a few additional Anglian settlers or ‘refugees’ from warfare or political unrest during the rest of the 9th century.

At the height of its development, ie the late 9th century, a beautifully carved stone cross grave marker was ‘planted’ in the churchyard in memory of an important Northumbrian person of high status, as much a political statement of power and Christian authority as simply marking a particular grave.

This is the only hard evidence we have of this period, since the early Anglian ‘chapel’ is no longer visible.

Viking raids on Lindisfarne monastery began in 793AD and then continued for some time around the coast of Cumbria and southern Scotland; having found good prospects for farming and trading, some began to settle down.

The Viking raiders were visiting the country between the Pennines and the Irish Sea in sufficient numbers to dislodge the local nobles and churchmen – as happened at Heversham.

Abbot Tilred, who was himself the son of a Bishop of Lindisfarne, together with his monks and a wealthy royal landowner, Elfred, abandoned the minster in about 902AD. Elfred was the son of Beorhtwif, King of Mercia from 839-852 AD, who was defeated by the Danes – perhaps Elfred had fled for sanctuary to Heversham - certainly he was very important because after he fled he was granted 12 vills or townships in Yorkshire by Bishop Cutheard. Tilred became Bishop of Lindisfarne in 925AD.

The local people were probably left to fend for themselves for a while, but again, within a few years, more Vikings came into the area, this time third-generation Scandinavians fleeing from violence in and around Dublin (called Irish-Norse). They were largely pastoralists, and many chose to move up the Lyth Valley to farm and settle in the fells and along the creeks and inlets of the coast, including around Milnthorpe (Ackenthwaite).

A proliferation of Norse names in our area suggests a considerable resettlement, but most of the Irish-Norse were already Christian and would continue to exercise their faith in some of the small chapels and bury their dead in the present churchyard.

St Martin’s Chapel, Martindale

There are no Norse artefacts in our immediate area, and in fact very little to help us understand how life continued until the coming of the Normans and Ivo de Taillebois as Overlord of Furness and first Baron of Kendale, who gave one third of the ancient manor of Heversham and its church to the Benedictine monastery of Saint Mary, York in 1090.

We know from the Domesday Book that there was only a tiny population to be counted, and those who were here would be subject to a new, harsh regime.

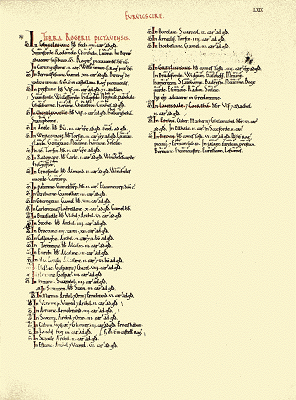

Domesday Book

By 1130AD, Heversham had its own priest and a much larger stone Norman-built church serving a wide area, evidence for which can be seen in the building today.

Next ~ The Heversham Cross